Meet the BVI’s Taino Indians

They gathered in large communal houses made of thatch and wood, and subsisted off the land and sea, taking only what was needed, living in harmony with nature. Long before Columbus discovered these islands in the name of Spain, before Dutch settlers erected the islands’ earliest forts and English planters grew sugarcane along its hillsides, the British Virgin Islands were inhabited by the Taino Indians, descendants of people from the Caribbean’s earliest Indian tribes who migrated to the Antilles from South America over 3,000 years ago.

The Zemi

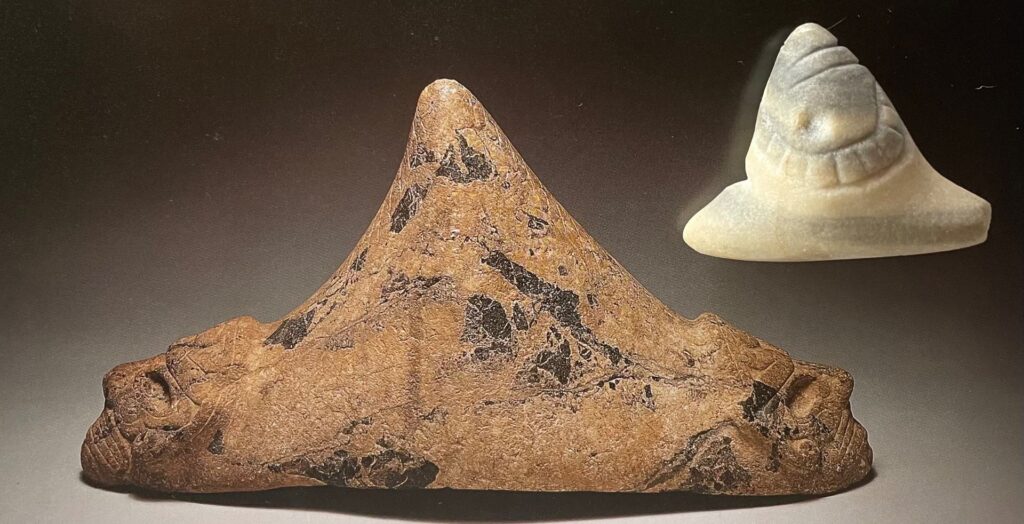

I first became interested in Tortola’s Tainos when my then eight-year-old son discovered a small triangular stone etched with an image of a fish (or so I thought) while hunting for shells on the Sand Spit on Tortola’s West End. At first it was puzzling: why would a stone have such a carving? But eventually I realized that it was most likely a Taino artifact and an astounding find.

As chance would have it, a group of archeologists from London University’s Department of Archeology were studying an Amerindian Village at Belmont adjacent to Long Bay beach on Tortola. I found the archeologists embedded deep in the area’s palm grove where they were excavating a shallow pit and sifting sand for artifacts. The expedition’s leader, Dr. Peter Drewett, was quick to identify my son’s discovery as a zemi, a stone representation of a Taino deity, and was impressed that someone so young could stumble across such an important find.

Remnants of forts and sugar plantations still dot the islands, vivid reminders of the islands’ colonial past, but there is little tangible evidence of the Amerindians who peopled the Virgin Islands for over 1,000 years. What does remain of their presence is primarily found in the archeological record. The remains of charcoal pits show where they cooked their food; the shells of whelks and clams, and the bones of small animals indicate what they ate. Pottery shards and ritual artifacts shed light on their lifestyle and religious beliefs.

At one time there could have been several thousand Taino Indians living on Tortola, spread out in dozens of small communal villages along the shore from Cane Garden Bay and Beef Island, to Long Bay on Tortola’s western end. Some, like a fishing camp in Paraquita Bay may have been temporary settlements – a place where villagers came to fish and hunt.

Others were permanent settlements like the lush and wooded area behind Long Bay beach which is now known as Belmont. Here there was a protected inlet fringed with mangroves where villagers could gather whelks, and a beach where they could launch their canoes to fish.

What they Grew

Community members grew corn, sweet potato and cassava in the area’s rich soil and cooked the cassava on clay griddles. They spun the cotton they raised into fiber using spindle whorls to create loincloths for the men and short skirts for the women. For cooking and for use in rituals, they formed pottery from clay which they incised with cross hatching, or decorated along their rims with adornos – figures of animals and deities.

At the western end of the beach, the triangular shaped hill referred to as Belmont Hill, would have abutted this inlet, and was a focal point of the village’s religious life. Here ritual objects for use in ceremonies as well as many household artifacts and tools from cassava griddles and bowls to stone tools have been found. There is evidence of the post holes, which would have once contained the wood supports for large communal round houses made of thatch. These finds depict a daily routine that was both sophisticated and spiritual.

Although earlier prehistoric tribes resided in the Virgin Islands from perhaps 2,000 BC, the Tainos were the most recent Indian culture to populate Tortola and neighboring islands. The Taino culture encompassed all of the Virgin Islands including Tortola, St. John, St. Thomas and St. Croix, as well as the larger islands of Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic where the communities were much larger and more highly developed.

A Ball Court

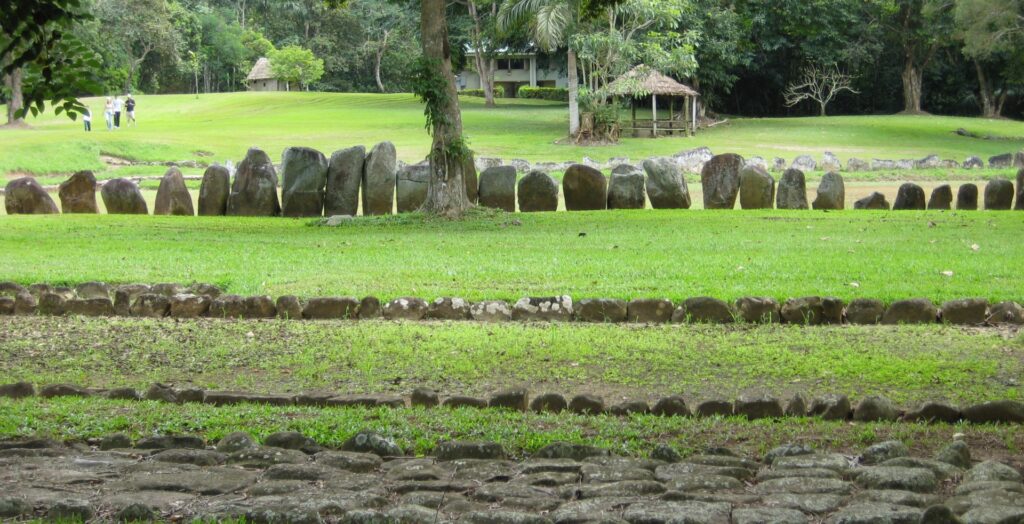

Dr. Drewett spent close to a decade excavating the site at Belmont in the 1990s and 2000s. His work painted a vivid picture of life there, initially as a village and later as a ceremonial area. In 2004, he and his team unearthed an astounding find – a Taino ball court 25 meters in length; nine of the dozens of stones that would have bordered the court were found, one of which was carved with a petroglyph of the sun.

These ball courts are an integral part of Amerindian religious life and are found at Taino settlements elsewhere in the Virgin Islands as well as on Puerto Rico and the Domincan Republic. In the Taino ceremonial sites at Tibes and Caguana, on Puerto Rico these ball courts had attained a high degree of sophistication. Nine ball courts and ceremonial plazas have been found at Tibes and ten at Caguana where many of the stones bordering the courts were carved with petroglyphs.

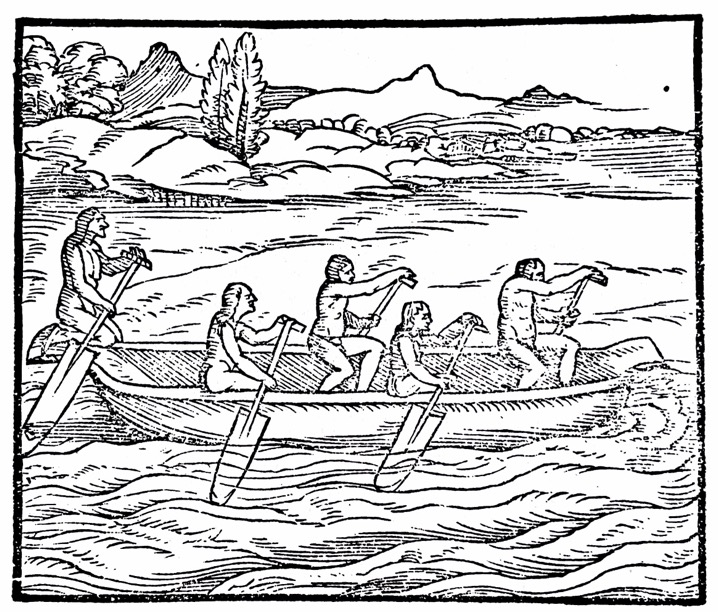

Columbus and other Spanish explorers, who first encountered the game at the end of the 15th century, recounted a spirited sport where teams comprised of ten to 30 players alternated serving a rubber ball which they kept in motion by bouncing it back and forth from their bodies to the ground within the court. Both men and women played the game, although separately. Spectators sat on stones or embankments, and the caciques and nobles on their stools – known as duhos.

Batey, as the Indians called the game, was both a recreational sport, as well as a grand religious ceremony, which would include dancing, drumming, singing and rattling. Great feasts would also be part of these rituals. These plazas may have been significant in other ways and played a part in marking the time of year. According to Archeologist Osvaldo García Goyco, “there is evidence that some of the plazas are orientated in relation to the equinox and solstice of the four seasons of the year.”

In Belmont, there would have been a single ball court, but it too was ceremonial. And like the Tainos at Tibes, the villagers at Belmont also celebrated the solstice. Central to the Amerindian religion was the worship of three-cornered idols or fetishes called zemies, like the one my son found. Representing their deities, zemies were usually made of wood, stone, bone or shell. But it was also believed that they lived in trees, rocks and other features of the landscape such as the triangular shaped hill that served as the site’s backdrop. During their digs, the archeological team unearthed a number of ceremonial artifacts, including a vomit spatula (used for purification rites) and two pairs of long polished stones aligned towards the center of Belmont.

Solstice Ceremony

On the solstice, the sun sets directly behind the hill, and in a stunning display, beams of light cascade down both of its sides, throwing a shadow across the stones. I watched this phenomenon with the archeologists one day, and was awed by the sight.

Tortola was not the only island here in the BVI with Amerindian settlements. A site at Cape Wright on the northeast coast of Jost Van Dyke has also revealed a trove of Amerindian artifacts. Dr. Brian Bates of Longwood University and a team of students spent several summers excavating the area, unearthing artifacts that included thousands of pottery sherds a stone ax, spindle whorl and an eye made from a shell which would have come from a wooden statue of a deity.

“Because people are no longer here to tell about themselves,” Dr. Bates explains, “we use their ceramics.” The Amerindians, he believes most likely migrated from the southeast, moving northwestward, perhaps because resources became depleted.

The Indians, who lived on Tortola and its neighboring islands, inhabited the area for many centuries, interacting with nature and leaving little imprint on the landscape. But their reign in the Caribbean came to an end soon after the arrival of the Spanish. When Columbus arrived there was likely Tainos in what is now The BVI, but he did not report on it. Soon after, the Indian populations in The BVI, as well as Puerto Rico, Hispaniola and other islands, fell victim to European diseases like small pox and measles, and by the harsh enforced labor inflicted by the Spaniards. Within a few decades the Indian population of the West Indies had been decimated.

The BVI Tainos Today

I often walk past the palm grove at Belmont and think about the people that once fished and grew cassava there. Sadly, the area is now overgrown. What once had been a vibrant Amerindian village, and an amazing prehistoric culture, is now hidden from view. But even so, their legacy lives on in many ways.

Many foods we take for granted and the words we use for them come from the Taino culture: sweet potatoes (batata), corn (maiz) and cassava (casabe) were all Taino foods; the Taino gave us the hammock (hamaca), the canoe (canoa) and tobacco (tabaco). Perhaps even batey may have been a forerunner of our modern game of football or soccer.

The Tainos also live on through inter marriage between the early Spanish settlers and Tainos. Today some people in Puerto Rico, as well as the Dominican Republic and Cuba still carry their DNA and continue many of their traditions.

These gentle people that lived here before Columbus had little impact on the lands they occupied, but a large impact on our everyday lives.

Read more about what became of the Taino Indians and how their culture and DNA survive today in this Smithsonian Magazine article “What Became of the Taino Indians.” See link below.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/what-became-of-the-taino-73824867/

More information on BVI history can be found at: